7 September 1875, New York, after an invigorating lecture to a bespoke, almost chic, crowd on the occult secrets of the Great Pyramids of Giza, a member of the audience, a bearded Civil War veteran, arose and proposed creating a society ‘for this kind of study’.

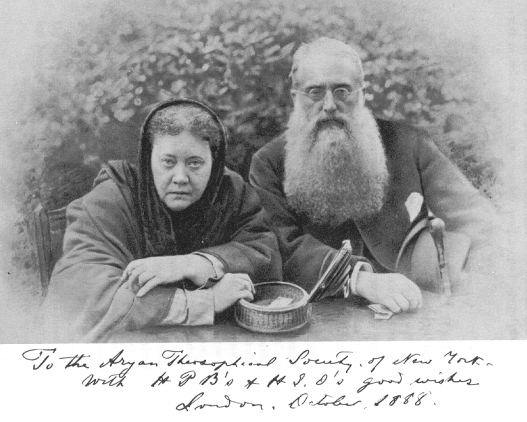

Colonel Henry Steel Olcott had had an abiding interest in spiritualism, but in recent years, this was galvanised into something more active when he met a charismatic Russian woman.

The audience agreed and together they helped form a nucleus of the Theosophical Society, an influential group with lasting social and cultural impact.

To tell the story of what happened in the fall of 1875, we have to go back multiple centuries to Roman Egypt. Here, texts were written which combined Greek philosophy and Egyptian religion mixed with a healthy dose of mysticism.

They were said to be ancient, dating back to the earliest days of civilisation and representing an original, uncorrupted truth. Their proposed author was Thoth, identified with the Greek god Hermes, and so they were called Hermetica.

These texts formed the basis of an important stream of occult thought, which surfaced and flourished at points throughout the centuries. For them was Bruno burnt, Kircher led astray.

They lent to Egypt a mysterious allure it never lost, even as the texts were scientifically dated and shown to be Roman period creations.

We skip forward a millennia and a half to Dnipro, now in the middle of Ukraine, then part of the Russian Tsarist Empire.

A young woman of minor aristocratic background became immersed in the occult through her great-grandfather’s library.

Helena Petrovna Blavatsky believed she had great powers and went in search of herself to develop them.

After a short marriage to a Russian Vice-Governor in Armenia, she travelled widely in the 1850s and 1860s.

The details are murky, but there is corroborating evidence that she was in Egypt, she almost certainly went around the Caucasus, Southern and Eastern Europe, and central Asia.

She was in Britain in 1851.

She told a later follower that she received a mystical visitation at the Great Exhibition in London. (In another version it was Ramsgate.) There she met a man of great spiritual power and insight, who she believed was a ‘master’.

Some say the person she met was Edward Bulwer-Lytton, the author of The Last Days of Pompeii.

She clearly had a wanderlust, even if the journeys are represented as a search for knowledge.

Although she claimed it, we can never know if she really made it to Tibet to learn Buddhism first hand from the lamas. The country was then closed off to Russian and British travellers.

It is possible, if unlikely.

Her biographer Gary Lachman thinks she had her first direct contact with Buddhism in Astrakhan.

But at this period of her life, Egypt was the abiding interest.

***

On her first trip to Cairo in 1851 she made friends with Paulos Metamon, a Coptic magician who possessed a large library.

An American she met on the trip later wrote that she tried to set up an occult research group but was told to delay this by Metamon.

She next returned to Cairo in 1871, possibly after surviving a shipwreck.

Settling in a luxury hotel, she tried to set up an occult study group, associated with a mysterious group called the Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor. It claimed an ancient lineage but was likely set up in the 1860s.

Blavatsky believed in ‘masters’, spiritually enlightened beings who guide humanity and could speak to individually gifted humans.

One of them, she called Serapis Bey, the name combining the tutelary god of ancient Alexandria and an official of the Ottoman Empire.

Serapis, in a letter to Olcott, described himself ‘not a disembodied spirit, [but] a living man’. (Goodwin, 291)

***

By the mid-1870s, Blavatsky was in New York.

There were many people, in the city, interested in the occult.

America had experienced a vogue for spiritualism, partly inspired by the famous Fox sisters who claimed they could channel the spirits of dead people.

One of these was Olcott, who met Blavatsky, while investigating spiritualism for a newspaper. They became very close during this time and Olcott eventually left his family to follow Blavatsky.

Another was George Felt, also a civil war veteran and inventor of telegraph devices and rockets. Felt’s other major interest was the ‘Egyptian proportion’ of the pyramids and its links to the Kabbalah and a wish to introduce Egyptian initiations into freemasonry.

It was Felt who gave the fateful lecture on the Great Pyramids in 1875 at which Olcott stood up and suggested the creation of a new society.

A vote was taken and passed by the 16 or 17 people present (including Blavatsky). After a short discussion about a suitable name, someone took down a dictionary and found ‘Theosophy’ by chance.

It was an old term, referring to those who believed they could attain a direct knowledge of god, often through mystical experiences. Blavatsky later said the name came from Alexandrian Philosophers, Philaletheians (Greek for Lovers of Truth).

It was the perfect name, with enough antique credence in the general but agonistic to particularities.

The new society was made official in November.

***

Olcott and Blavatsky moved in together in the ‘Lamasery’, a smoked-filled apartment in Hell’s Kitchen hung with taxidermized animals and various bric-a-brac.

This period of her life culminated in her first major work, Isis Unveiled, published in 1877.

Blavatsky never liked the book’s title.

It was going to be called The Veil of Isis until she was told another book with that title was about to be published.

It comes from an epigraph on a statue of the goddess in Sais, recalled by Plutarch, “I am all that has been, all that is, all that shall ever be, and no mortal has lifted my veil’.

Plutarch had a very philosophical reading of the Isis myth and so we should take passages like this carefully as historical facts of ancient beliefs.

Nevertheless, it had become an important image of Egypt in the public imagination.

Blavatsky worked on the book with Olcott, recalling passages from other texts in her memory.

It is a complex and large book and likely rewards close reading.

Gary Lachman notes her ‘hectoring, blustery style … didn’t want to convince the reader so much as to bowl him over’.

It contains a mass of allusions and references, but the central thesis is that all religions spring from the same original source, an ancient religion which is Hermetica.

It was also a massive success.

***

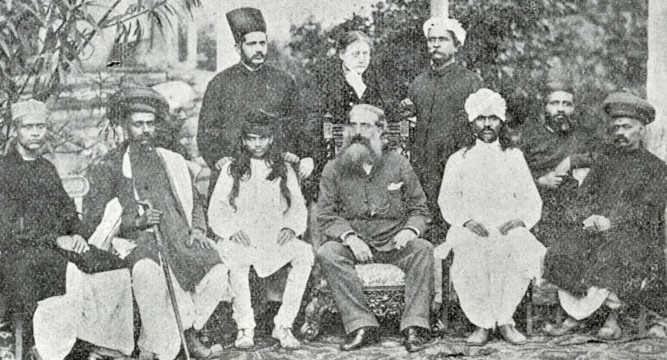

Following publication, Blavatsky and Olcott travelled to India in 1879.

Here they mostly avoided the British military leaders who occupied the country and engaged directly with Indian religious leaders.

They both converted to Buddhism, taking the Five Vows. Blavatsky later claimed she had always been a Buddhist.

Olcott became more and more involved with Buddhism, becoming an important figure in India.

Their trip is seen as a critical moment when the focus of Western esotericism moved from Egypt to the subcontinent.

Blavatsky’s second major work, The Secret Doctrine, published in 1888, popularised ideas of reincarnation and karma, a direct reversal of what she had written in Isis Unveiled.

In this new guise, the society helped open up roots for later popular trends like yoga and meditation.

A lot more could be said about the later history of the movement and its leaders, not all of which is exemplary, but that is another story.

In her colourful life, Blavatsky revolutionised occultism, merging different traditions into a persuasively uniform and expansive system.

Together with figures like Olcott, she popularised Indian religious traditions, offering new ways for people in the west to engage with spiritualism.

Even if you don’t subscribe to the tenets of Theosophy, this topic rewards study and reveals important lessons about Nineteenth century thought and the legacy of ancient Egypt.

This post borrows heavily on Madame Blavatsky: The Mother of Modern Spiritualism by Gary Lachman and The Theosophical Enlightenment by Josceylyn Godwin.

Feature image: Madame Blavatsky (Public Domain via Wikimedia).