One of the most extraordinary items in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge is a ceramic white sphinx.

It is dated from the 1750s and is said to depict the actress Margaret ‘Peg’ Woffington. It reveals so much about the eighteenth century.

Similar items are found in other museum collections around the world including a painted statuette from the British Museum.

Bow ceramics

Although we do not know the designer, the figure was made by the Bow porcelain factory. The company received a patent in 1744 for discovering a new technique for producing fine Chinese style porcelain. This was a very lucrative market. Chinese producers not only had centuries of experience, but also access to the perfect soil. The spread to European countries was inextricably linked to the rise of international trade and colonialism. Porcelain was often used to drink tea, a luxury food stuff, also from China. Indeed the Bow Factory, located in what is now Stratford High Street, was called ‘New Canton’. Canton or Guangzhou was the major port for exports of tea and porcelain at the time.

Modern scholarship has identified that the unique item which set off the Bow production was a new soil extracted from land belonging to the Cherokee nation, today in the state of Georgia. The Cherokee called it unaker. Twenty hundred weight was brought to the UK.

When the unaker ran out, research has shown, the producers replaced it with ‘pipe clay’.

Bow has a mixed reputation.

Daniel Defoe described the production in 1748, writing “They have already made quantities of teacups, saucers &c. Which by some skilled persons are said to be little inferior to those imported from abroad”. While a later scholar sniffs the items were ‘not of the same high standard as the contemporary products of Chelsea, have a distinct character of their own’.

The figurines are particularly praised by modern collectors.

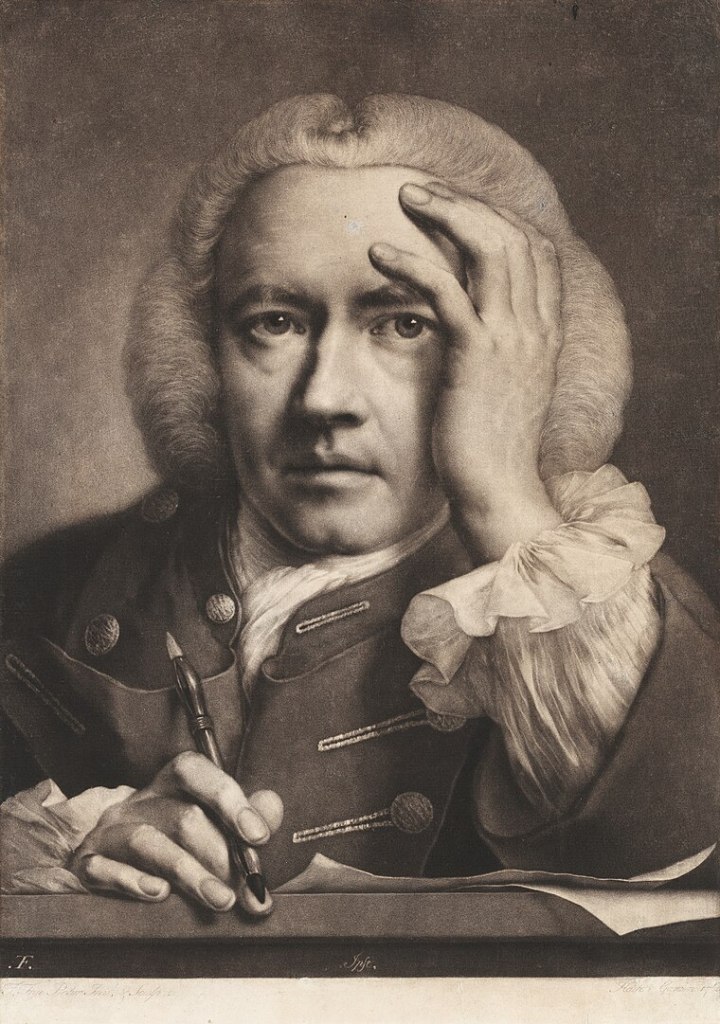

One of the initial founders, Thomas Frye, was a Mezzotint engraver of some distinction and may have designed the sphinx, as well as other figurines.

Peg Woffington

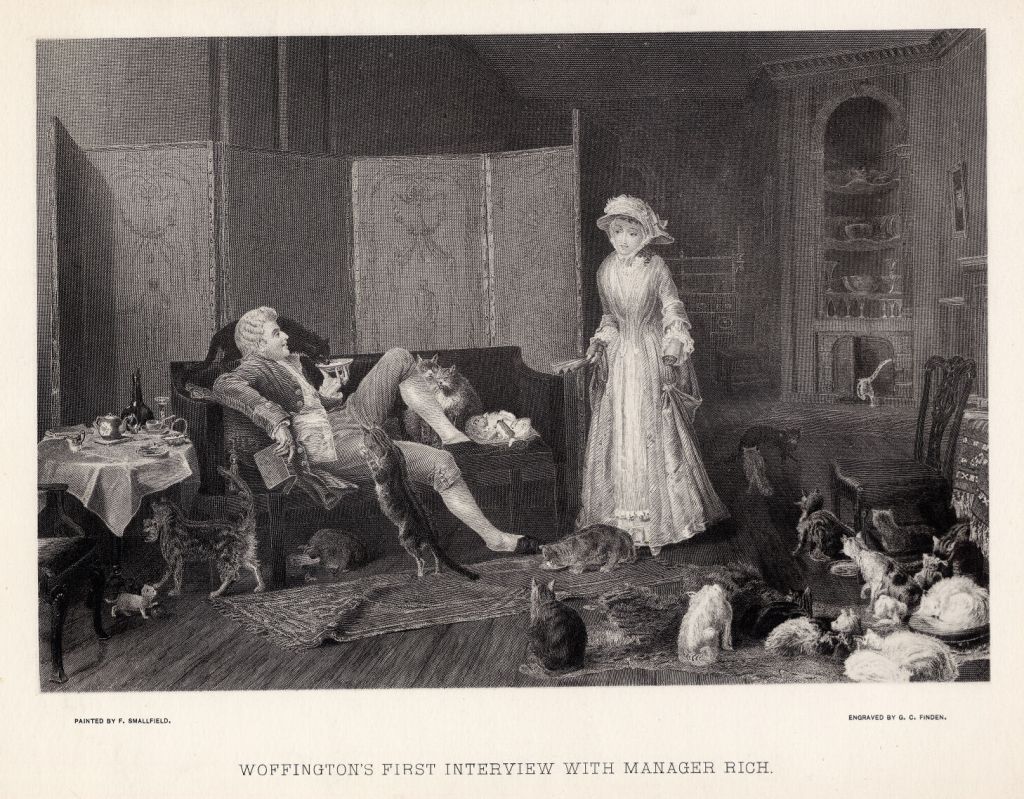

Margaret ‘Peg’ Woffington was a talented Irish actress who became the toast of the London theater.

Reading her life today, you get a strong sense of personal drive and vivacity that feels very contemporary. ‘She was not ‘respectable’”, one of her modern biographers has written, ‘few eighteenth-century actresses were’. (Dunbair, 1) A more salaciously minded author wrote: “It is as the merry magdale with the heart of gold rather than as a brilliant and accomplished actress that Peg Woffington appeals to the imagination” (Trowbridge, V) While she never married, she was part of several long term relationships, but this and her association with the stage kept her outside of polite society.

Growing up impoverished, she was sent out to work while young, selling salads in the streets of Dublin. Here, she may have learnt the quick repartee and wit that held her in good stead. She was talent spotted and got her first start in drama playing in the ‘Lilliputian Theater’ made up of young children playing adult roles. She visited London with this troupe, acting as Polly the heroine in the Beggar’s Opera.

As an adult, she made her name in ‘breech roles’, playing male characters. Her first break was playing the role of Silvia in Farquhar’s Recruiting Officer. This character cross-dresses as a soldier called ‘Jack Wilful’, and after several cheeky adventures, marries his love. Peg’s fame was made playing the role of Sir Henry Wildair in Farquhar’s The Constant Couple. It was widely felt that the actor Robert Wilks had made it his own and no other male actor could play it following his death. Peg made the role her own. One review wrote:

“In the well-bred rake of quality, who lightly tripped across the stage, singing a blithe song, and followed by two footmen, there was no trace of the woman. The audience beheld only a young man of faultless figure, distinguished by an ease of manner, polish of address, and nonchalance that at once surprised and fascinated them.”

From Dunbair, 61

Poems were written:

That excellent Peg

Who showed such a leg

When lately she dressed in men’s clothes –

A creature uncommon

Who’s both man and woman

And the chief of the belles and the beaux!

Another poem referencing her acting career concluded with the lines ‘Another ended ‘And who to Polly scorned to fall / By Wildair, ravaged, die’. (both poems from Dunbair, 39)

Great dames of the theatre

Bow Ceramics also made figurines, including the actors Henry Woodward and Kitty Clive from their performance in Garrick’s play Lethe.

This is ironic, as it was said of Kitty and Peg that ‘No two women in high life, ever hated each other more unreservedly than these two great dames of the theater”, (Trowbridge, 156, Dunbair, 153).

Peg came out best from their off stage interactions:

But though the passions of each were as lofty as those of a Duchess, yet they wanted the courtly art of concealing them, and this occasioned now and then a very grotesque scene in the Green-room. Woffington was well-bred, seemingly very calm, and at all times a mistress of herself. Clive was arrogant, high-tempered and impetuous. What came uppermost in the mind she spoke without reserve. Woffington blunted the sharp speeches of Clive by her apparently civil, but ever-keen and sarcastic replies. Thus she often threw Kitty off guard by an arch severity which the other could not easily parry.

The writer continues. Kitty possessed ‘ a volume of language and a command of vituperation … that was not hindered by delicacy nor confined by wit’.

Dunbair, 153

On one occasion a physical fight broke out between the pair in the Green Room, which soon grew into a mass brawl between each woman’s supporters. An eyewitness reported two men fighting ‘Let go my jaw, you villain!’ and ‘Throw down your cane, sir!’, while the actors still on stage at the end of the play ran back to join the fun or stop the fight. A print from the time shows the scuffle at the more decorous point that it was broken up.

This fight was a draw, but Peg long regretted that she had lost her cool.

Peg was a well connected woman, and even if court society didn’t welcome her, she had associates among the aristocracy. She paid for her sister’s education and enabled her to marry well. She also helped the gorgeous Gunning Sisters be introduced into society, by lending them her dresses. Horace Walpole described them thus:

There are two Irish girls of no fortune, who are declared the handsomest women alive. I think there being two so handsome, and both such perfect figures, is their chief excellence, for singly I have seen much handsomer figures than either.

Dunbair, 189

It has been suggested these two were the model for the sphinx.

The Rococo sphinx

The most intriguing thing about the ceramic is its sphinx-shape.

Sphinges had long been associated with Ancient Egypt in the West. They had been known in Rome from the late medieval period, inspiring lions and other beasts, in churches. During the Renaissance and Baroque period artists depicted them in paintings and sculpture. By the eighteenth century, sphinges had transformed into feminine forms.

For example, the sphinx by Ferdinand Tietz located in front of the Electoral Palace in Trier, the sphinx Veitshochheim castle in Bavaria and the sphinx in a statue by Johann Wolfgang van der Auwera also in Veitshochheim all depict a half lion, half women dressed in a flowing skirt. While the pair of sphinges in Prince Eugene’s Belvedere in Vienna have the addition of wings. While the sphinges in Syon Park, London, bear a family resemblance to these continental examples.

Pevsner and Lang wrote the sphinges are ‘are so common and often look so frankly Rococo that one tends to forget their Egyptian ancestry’.

The Peg Woffington Sphinx is obviously of the same family.

Summary

The question remains then why was Peg depicted as a sphinx? It is not clear. No one from Bow Ceramics left any notes on this figurine, so we must use guess work. Likely it reflects the popular style of the time. The use of Peggy as a model reflects her stature as the preeminent type of female beauty. Possibly her free life meant she was not suitable for the types of ‘polite’ houses that would buy Bow ceramics and so had to be semi-disguised.

Perhaps, but I prefer to think that like the sphinx she transcended the mere human shell to become an immortal figure, untrammeled or untamed by the capricious rules of man.

Read more

Elizabeth Adams and David Redstone (1991), Bow porcelain

Peter Bradshaw (1992), Bow porcelain figures circa 1748-1774

Janet Dunbair (1968), Peg Woffinton and her world

Geoffrey Freeman (1982), Bow porcelain

Michael Noble (2018), Bow porcelain

W.R.H. Trowbridge (1912), Daughters of Eve