Some people have found god at a baseball game, others while eating a demi pollet in a Côte Brasserie.

I once experienced a fleeting sense of the more than human, at Epidaurus, the sanctuary of Asclepius the Greek God of Healing.

As I walked through the ruins, in the gentle April sun, looking at the purple flowers that ran across the entire site and listening to the murmur of the insects and the songs of birds in the trees above, I thought to myself, if I was a believer in the old gods, then I would see them here.

I am not a ‘pagan’, but the reflection brought me a sense of peace, a glimpse of another world.

Beauty can do powerful things.

In his first monograph, Hugo Shakeshaft (A.W. Mellon postdoctoral fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, National Gallery of Art, Washington DC) explores the Greek concept of beauty in relation to the gods, through the artworks, literature and architecture of the Archaic Period.

Thinking about beauty and the gods raises important questions on Greek belief systems.

Gods have to be similar to humans to be understood and recognised by them but different enough to be seen as gods.

Beauty, Shakeshaft writes, is a form of intermediary between human and divine.

He draws on the scholarship of Albert Heinrichs who argued that Greek gods had three attributes: immortality, anthropomorphism and power.

Each of these is related to beauty.

The gods were not just immortal, but ageless.

Youth and beauty were synonymous in antiquity.

This perhaps avoids the troubles of the Struldbruggs, a group of people encountered by Gulliver on his travels, who cannot die, but still age, physically and mentally, slowly withering into hyper-senescence and watching funerals go past with envy.

Anthropomorphism, human shape, was also important.

As Shakeshaft points out, the gods appeared in other forms, animal or natural, but it is in human disguise that they were most often depicted (or made themselves manifest to humanity).

“When gods reveal themselves…”, he writes, “beauty is often what mortals see and wonder is what they feel”.

Certainly some gods used this to their own ends.

Several gods had relations with humans. Zeus is still notorious for it.

The gods liked beautiful humans, Shakeshaft thinks, because they looked the most ‘godlike’.

Here, we get to the final attribute: power.

Shakeshaft writes: “The inherent power of beauty and the inherent power of the gods further cement the bonds between them.”

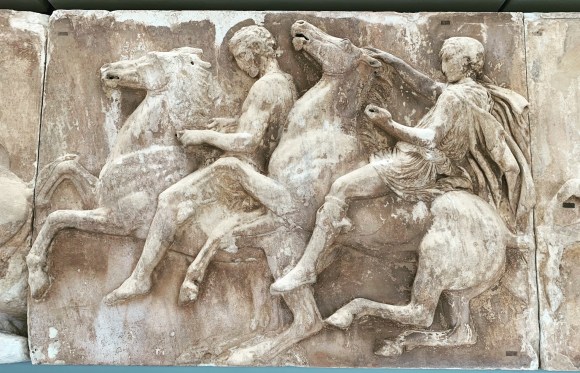

Gods are big and shiny in Archaic Greek Literature, while the Homeric heroes lived in a world in which everything was magnificent and gorgeous and temples were built specifically to be imposing.

“This is not merely because large size increases visibility. It is also thanks to an essential facet of beauty. That is to say, whatever their physical properties, such as grandeur and radiance, and whatever their effects, such as delight and wonder, beautiful things demand to be noticed. They stand out, attract and command our attention.” (page 286)

But the Greeks avoided some of the brashness of Trump Towers by a certain sureness of touch and an aesthetic sensibility.

The Greeks had an eye for beauty, natural and manmade.

Their temples were built to accentuate the natural beauty of a particularly gorgeous bit of the world.

The gods themselves subsumed the meadows, groves and streams of antiquity.

“Bearing the divine marks of beauty and vitality”, Shakeshaft writes, “such places appear enlivened with the possibility of divine manifestation”.

As Shakeshaft recognises, there are other forms of godly beauty.

“Never cross the sweet-flowing water of ever-rolling rivers afoot until you have prayed” Hesiod wrote in the Works and Days, 737.

Trees and plants could bear witness to the presence of the gods and sacred groves are known from many sites.

A palm tree in Delos was said to have been used by Leto as support while giving birth to Apollo in the Homeric Hymns and to have been planted by Odyesseus.

Even if the mythic chronology doesn’t quite work out, this tree was mentioned by several historical authors including Cicero, suggesting it retained some importance for centuries.

with a view over the Argive plateau.

Ultimately beauty comes with a cost.

A focus on aesthetics can obscure the economic base and the production of it, but reveals something of the world view of other cultures.

It also provides a foothold into an understanding, a sense of shared values, for better or worse.

And we are still brought closest to the Ancient Greeks and their gods when we study the design on a vase, gaze at a statue or wander through their sacred sanctuaries, still beautiful after all these years.

Read this book. It’s beautifully written and presented and provides a fascinating new reading on an important phenomenon of antiquity.

Beauty and the Gods: A History from Homer to Plato by Hugo Shakeshaft (Princeton University Press, 9780691250205), $49.95/£42.00