Gnosis, the ogdoad, syzygy and Linda Ronstadt.

Last year, scientists announced they had discovered a new color.

By shining a strong laser in people’s eyes, they were able to see a bluey-green tinge never seen by human eyes.

I swear I worked with someone with a cardigan in the same shade.

The image shared in the articles looks suspiciously like the particular hue of turquoise sold all over the world in Urban Outfitters in the early 2010s.

But the scientists proudly assured us that humanity was on the cusp of something completely world changing, yet it was not a new experience.

02-03-74

In February and March 1974, the American Sci-Fi author, Philip K Dick experienced a series of mystical events. (I call them events as they were more than just internal experiences.)

In one of the more dramatic moments, a laser beam of intense pink energy hit him squarely between the eyes, like Saul on the road to Damascus.

A shade of pink unlike any he had seen before.

Certain facts were revealed to him.

- He identified a serious medical issue in his son, which was undiagnosed by medical experts, although his wife had long told him she suspected it

- He was able to negotiate for $3000 more in royalties from his publisher.

- He shaved his beard more neatly and changed for a time from wine to beer.

At points, he said an ‘AI Voice’ gave him this advice.

More importantly, it revealed this world was a false illusion, time itself did not exist and ancient Christians armed with advanced technology were breaking through the prison of reality from another dimension.

He spent the rest of his life trying to explain this visitation, initially through his novel VALIS.

***

I first read VALIS at 16.

On a very boring summer holiday, I read it in an empty park, sat on a metal slide and got sunburn.

And it blew my mind.

Like many books that hit you in adolescence it has stayed with me and seen through the blurred glasses of hindsight, it has shaped my life in unusual ways.

Not least by introducing me to Gnosticism and the wide variety of forms that early Christianity took, a subject I went on to study many years later.

I have read it several times since and gleaned different things on each occasion.

I thought it would be valuable to re-read with the ‘expert knowledge’ I have gained through academic study of ancient religions, a life choice as bizarre as any made by Philip K Dick’s characters.

***

What happened in early 1974?

Phil struggled to answer this question across several works.

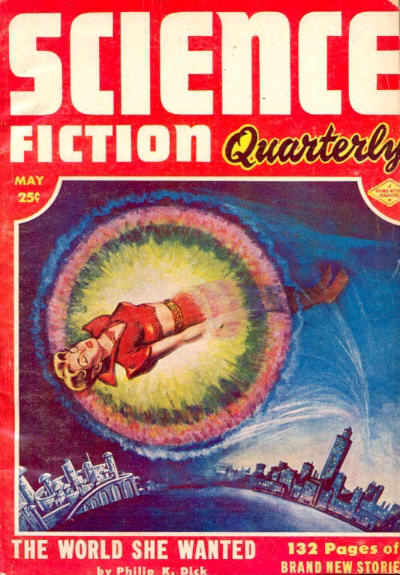

The novel VALIS is thematically and narratively linked with several other later books including The Divine Invasion and The Transmigration of Timothy Archer (collectively called the Valis Trilogy).

Radio Free Albemuth was published posthumously. It was his first attempt to novelise his experiences. It is interesting to compare this novel with VALIS in terms of themes, how he rationalised them at different points, but as a novel it feels insipid by comparison.

Phil also spent several years writing notes to explain his reflection on 02-03-74, as he termed his mystical experiences.

He called this work hisExegesis. A selection was published at the end of VALIS, with further separate editions published after his death in 1991 and 2011. The 2011 version is an intimidating tome. At nearly a thousand pages, it is best left for retirement.

Exegesis is a term normally used for an interpretation of a spiritual text which explains his sense of what the experience was, a form of cosmic information download.

Taken together these works provide a comprehensive narrative of what he believed happened to him.

Although there are subtle differences in each book, themes and images repeat like motifs in the classical music Phil adored.

***

02-03-74 was a profound experience.

But the source, the nature and the reality of the visitation confused him.

He used various names for it including Zebra (as he felt it came from an entity hiding in plain sight, like a Zebra) and VALIS (or Vast Active Living Information System, a synonym of the Logos reason, as expressed in the Gospel of John) or Sophia (divine wisdom).

He saw this entity as a projection of divine truth into an illusory world built by a false creator god.

“Basically”, a character in VALIS (essentially a self-portrait) cheerfully explains to his psychologist “my doctrine is Valentinian, second century CE”.

Valentinus was a major Christian thinker, taught by a disciple of St Paul (according to Clement of Alexandria).

At the heart of his theology, was the figure of Sophia who fell from another reality (the pleroma, the fullness), becoming the mother of the demiurge, the creator of this world, identifiable with the Old Testament God.

Sophia, like humanity in general, still has a divine spark hidden within.

The aeons from the higher realm call out to us. But we are trapped in a false reality, a prison, created by the demiurge.

Fat tries to explain to his psychiatrist.

‘Okay’, Fat broke in, ‘but that’s the creator deity, not the true God’.

‘What?’ Maurice said.

Fat said, ‘That’s Yaldaboath. Sometimes called Samael, the blind god. He’s deranged.’

‘What the hell; are you talking about?’ Maurice said.

‘Yaldaboath is a monster spawned by Sophia who fell from the Pleroma,’ Fat said. ‘He imagines he’s the only god but he’s wrong. There’s something the matter with him’ he can’t see. He creates our world but because he’s blind he botches the job. The real god sees down from above and in his pity sets to work to save us. Fragments of light from from the Pleroma are -’

In the novels, this divine emanation of truth sometimes comes from a satellite, from a different solar system, or from the caves of Palestine or Egypt.

Qumran and Nag Hammadi

One of the things that probably drew me to VALIS was not just the playfulness of unreliable narrators and shifting realities, the druggy, sexy, sleazy ambience of 70s California, but the theme of early Christianity.

I was brought up in the faith. Loosely Protestant: Methodist, although I attended Church of England Schools and I’m now more agnostic.

A lot of people have been thinking recently about what it means to think about Ancient Rome.

Is it imperialism, military glory, even Christian theocracy?

For me growing up, an important source of my image of Rome developed from this low church background.

Rome was the power that persecuted the Christians.

This theme was repeated in film, books and on TV.

When I first read that the Roman Empire ‘converted’ to Christianity, probably in the Usborne Guide to Ancient Rome, I was a little shocked.

(The other thing that drew me to Rome at a young age was the weirder stuff like Caligula, but that’s a different story).

It was through reading VALIS that I first learnt there were wildly different forms of ancient Christianity, with their own claims to textual authority.

This blew my mind.

***

There are different sources of religious authority:

- Organisational – like the Roman Catholic Church

- Textual – via canonical texts and traditional readings taught through schools,

- Visionary – the claim to a direct link to the divine. There is an important Biblical authority for this in St Paul.

Part of Phil’s mystical experience was visionary.

It was, to use a technical term, apocalyptical,

Apocalypse as in revelation or disclosure, the uncovering of one level of reality for a deeper one.

He saw first century Rome superimposed over the California of the 1970s.

A sign that the contemporary world was false.

In VALIS, this sounds more like flickering white villas on the distant hills. Horselover Fat, the main character, sees “ancient Rome superimposed over California 1974”.

It’s clear from other records that this was more visceral.

“Rather than me being back in the ancient world,” a character explains In Radio Free Albemuth, “Rome had revealed itself as the underlying reality of our present-day world”.

Phil said he saw children playing in a playground with wire netting and visualised Christians held in prison awaiting death in the arena.

Although he lived his whole life in California, and rarely left it, Phil was not so hot on his home state.

He called this Rome-California the Black Iron Prison.

It’s most pervasive symbol was Ferris F Fermont (FFF or 666), a stand-in for President Richard Milhouse Nixon, a native of Orange County.

If Nixon/Fermont is antichrist, struggles against him took an apocalyptic edge.

***

The merging of the ancient and modern was a key part of Phil’s experience.

He felt another personality, a figure he called variously Fire Bright, James or Thomas, a first century Christian who has access to a secret form of knowledge shared directly by the Apostles.

This figure was both separate to Phil and part of him.

It explained why, during an acid trip, Phil spoke a language he didn’t know.

The actual language seems to change in retellings from Latin to Koine Greek, German to Hebrew. (Phil was able to read Latin and was functionally fluent in German.)

***

The source of this figure varies in the different novels, but in VALIS, Thomas is awoken when Phil saw a woman wearing a fish symbol.

Without giving away too much of the ‘plot’, Thomas was one of the earliest Christians, with access to teaching hidden from non-believers.

When the Romans destroyed the Second Temple in the Sack of Jersualeum in 70 CE, this teaching disappeared from the earth.

In Phil’s estimation it was linked with the Nag Hammadi Library and the Dead Sea Scrolls, two sets of religious texts discovered after the war.

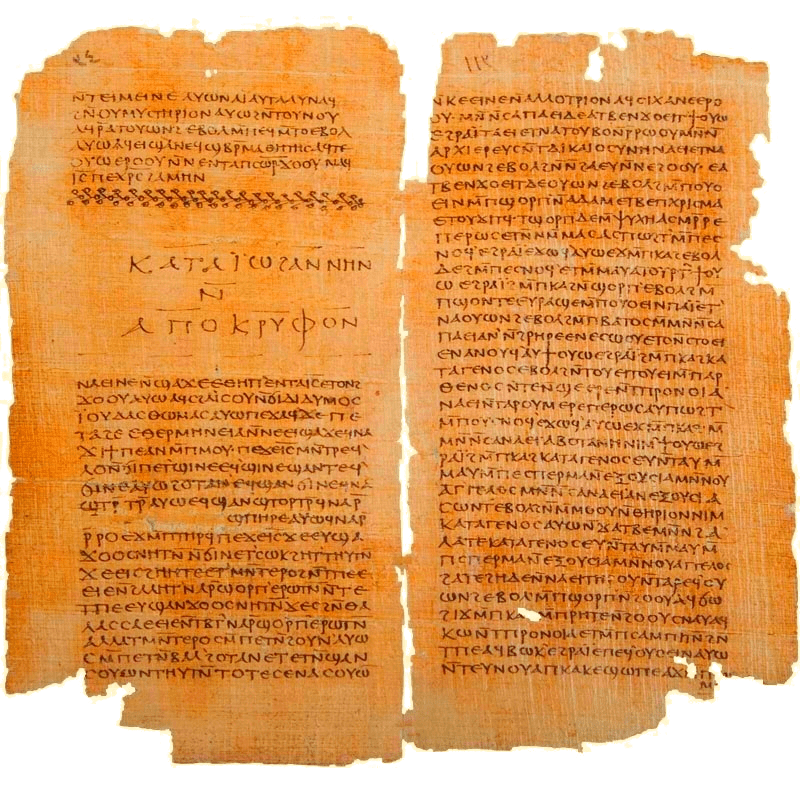

The Dead Sea Scrolls are more famous than the Nag Hammadi Library, the name given to a collection of twelve (and a bit) books, with 52 texts found in Nag Hammadi, Egypt.

Many scholars believe the books were buried following the standardisation of the new testament canon by Athanasius, Bishop of Alexandria, in the fourth century CE.

Together, the texts represent widely different teachings and forms of Christianity, some of which were only previously known through the testimonies of their critics.

For example, Ireaenus of Lyons and Epiphanius of Salamis both saw Valentinus as a heretic. (Clement of Alexandria was more ambiguous.)

But, in the Nag Hammadi Library, we found original texts which reflected some of their reports, and may have been written (or used) by groups connected to Valentinus.

A common thread is the belief in secret teaching withheld from ordinary followers.

“Unto you it is given to know the mystery of the kingdom of God: but unto them that are without, all these things are done in parables”

In one reading, this teaching took place after the death of Jesus. Many of the books in the Nag Hammadi Library claim an authority from Christ through biblically attested figures.

For example the Gospel of Philip may have been used by ‘Valentian’ groups.

The role of Christ is complex in Valentinian thought. In one version, the spiritual Christ forms a syzygy (a pair) with Sophia and projects the worldly Christ.

This teaching opens up a docetic reading: The idea that Jesus was either a spiritual projection or that the divine aspect was imbued to Jesus during baptism and disappeared at the crucifixion.

This is complex stuff, but as you imagine it has important connotations for how you see Christ.

Bishop Pike

What the hell, then, was an edgy Science Fiction Writer doing, messing about with advanced theology?

I blame one man.

Bishop James Pike.

Phil had long investigated themes of reality and illusion, power and resistance, but his abiding interest in early Christianity developed through his friendship with Pike, the Episcopolian Bishop of California.

Pike was a colourful figure, drawn to the fringe elements of belief, including spiritualism.

He was even tried for heresy.

The two men knew each other through Maren Hackett, a friend of Phil, with whom Pike lived openly in an extra marital affair.

Two of the novels say he used the Discretionary Fund to pay for the meals and shared apartment with his partner.

Phil later married Maren’s daughter, making the couple essentially his parents-in-law.

Phil and Maren also joined Bishop Pike at seances as he tried to contact his son who may have killed himself.

Pike wrote a book about his experiences at these seances in 1966 which damaged his reputation.

In 1967 Maren herself took an overdose and died.

She haunts all four novels. VALIS starts with ‘Gloria’ phoning up the novel’s hero asking for Nembutals (a sedative drug).

In 1969, Pike died in Israel, having taken insufficient liquid for a trip to the desert.

He took two bottles of coke, spitefully picked up by Joan Didion in her portrait of Pike (The White Album) as one of the details “which lift the narrative into apologue”.

***

Phil believed/half-believed that Pike was executed.

In an excerpt from his larger Exegesis, quoted in Valis, it is written:

#15 The Sibyl of Cumae protected the Roman Republic and gave timely warnings. In the first century C.E. she foresaw the murders of the two Kennedy brothers, Dr King and Bishop Pike. She saw the two common denominators in the four murdered men: first, they stood in deference of the liberties of the Republic; and second, each man was a religious leader. For this they were killed. The Republic had once again become an empire with a caesar. ‘The Empire never ended.’

The murderer is named in Radio Free Albemuth: Ferris F Fermont, the president who in that novel has masterminded an authoritarian take over of America. In VALIS, divine forces intervene to prevent Fermont’s / Nixon’s takeover through the threat of impeachment. It is implied in the novel that he may somehow be connected to Pike’s death.

***

In The Transmigration of Timothy Archer, his final book published while alive, Phil responded to Didion’s version of the Bishop in the character of Timothy Archer.

Archer is an intriguing character, a bit of an episcopal hot mess.

He marched with Dr King in Selma and seeks to expand his mission in San Francisco, by commissioning a rock mass led by a popular band.

But he is careless with the people around him, never picking up the shirt ties that he dropped.

Phil and Pike enjoyed debating theological ideas, pushing each other to be more expansive and obscure.

***

In this novel, Archer introduces the idea that the community at Qumran (the Dead Sea Scrolls community, identified by many as Essenes) used a psychoactive mushroom for religious ceremonies.

During the sack of Jerusalem in 70 CE, Roman forces destroyed this source.

Timothy Archer understands the mushroom as the Anokhi, the ‘I am’ of Jewish religion, the logos of Christianity.

“If I find the anokhi”, he tells his daughter-in-law, “I will have access to God’s wisdom. After it has been absent from the world for over two thousand years”.

The idea was first put forward by John Allegro, a scholar working on the Dead Sea Scrolls, in his book The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross.

Although I think we should be open to the idea of mystical practices in some groups within early Christianity, this idea has not gained much support.

In the immortal words of Wikipedia the theory ‘brought [Allegro] both popular fame and notoriety, and also complicated his career’.

In fact, his scholarly reputation was almost destroyed.

But it takes us back to an exciting period when an expansive state supported scholarship met cutting edge technology at a time when Christianity was still revered and religious history of enough interest to be published in popular books.

***

When I first read VALIS, I saw Bishop Pike as an ironic figure.

One of the ways that Phil deflects some of the intensity of the novel.

But it becomaes clear that Phil was profoundly affected by the loss of someone who was both a friend and spiritual comrade (if not father figure).

Ancient mystery cults

I was once told there were two plots: the siege and the quest.

Every story, every novel, every film, however long, however complex, however zany, meets one of these two narratives.

VALIS is a quest.

But more than Moby Dick (the Journey out) or the Odyssey (the journey home), it resembles the initiation rites of antiquity (the journey within).

***

In 1972, Phil moved to Orange County, psychologically broken from a harrowing stay in Canada. He arrived with a bible and a cardboard box tied with an extension lead.

Although the OC was the stomping grounds of his adversary Nixon (Ferris F. Fermont), here he formed close friendships with a group of young sci-fi Authors.

VALIS fictionalises the discussions they had on Thursday evenings.

In the novel, David is Fat’s Catholic Friend. Always conciliatory. He was based on Tim Powers, author of classic time travel tale The Anubis Gates.

The cynical and irascible Kevin, was based on K.W. Jeter, the atheist of the group. If he ever met the single ultimate creator of the universe, he said he would hold out his dead cat and ask them to explain why they allowed death.

The final member of this group is Sherri Solvig, more of whom later.

It was a fun atmosphere.

Phil, having discovered a new idea, would bring it over to Tim’s house.

Tim later said he thought his friend shared the most outlandish ideas just to get a rise from him.

In real life, the group took the same position formerly held by Bishop Pike, allowing Phil the space to explore and vent his ideas.

In the novel, they form the Rhipidon Society, who eventually set off together on adventures to seek the answer to their spiritual questions.

***

What I remembered from earlier readings was a deep engagement with gnosticism, ancient mysticism and classical myth.

Re-reading, I realise the book is almost polyphonic, quoting Nag Hammadi one moment and then opera.

“It all had to do with time. ‘Time can be overcome,’ Mircea Eliade wrote. That’s what it’s all about. The great mystery of Eleusis, of the Orphics, of the early Christians, of Sarapis, of the Greco-Roman mystery religions, of Hermes Trismegistos, of the Renaissance Hermetic alchemists, of the Rose Cross Brotherhood, of Apollonius of Tyana, of Simon Magus, of Asklepios, of Paracelsus, of Bruno, consists of the abolition of time.

That’s an impressive list of people and ideas.

I’m not totally sure what Serapis has to do with time specifically. Although, the goddess Isis herself, at the end of a first person praise poem from the first century CE, says “I overcome fate”.

Phil’s understanding of the mystery religions, reflects not just contemporary scholarship (heavily influenced by Mircea Eliade), but also New Age-y California.

Eliade was a major scholar of rituals, such as the Eleusinian Mysteries, seeing links between vastly different cultures. He argues they helped participants come into contact with the divine (or aspects of the divine).

There are tendencies to link Osiris with Christ, based on ideas of ‘Dying Gods’ or ‘Oriental Cults’, popularised by JG Frazer in The Golden Bough who argued that there was an original vegetation ritual linked to a sacrificial victim, which played out in later myths, religions and rituals.

Certainly ancient religions drew on each, intentionally or unintentionally. But this does not mean there was a single original myth or reason for myth.

These passages give a sense of Phil as a renaissance man.

His daughter Laura said “His apartment is full of bibles and religious books, encyclopedias and books of science fiction. Lots of records, especially Wagnerian opera” (Sutin, p. 262).

Several friends noted that he obsessively read the encyclopedia, perhaps uncritically drawing any interesting element into his overarching theory.

He also visited occult bookshops, buying piles of books.

***

Timothy Archer is criticized as ‘Lost in meaningless words … Flatus vocis, an empty noise”.

Words I think Phil would apply to himself at times.

“You know how I am with theories,” Philip K Dick, a character in Radio Free Albemuth, tells another character (who is the actual Philip K Dick stand-in). “Theories are like planes at LA International: a new one along every minute”.

At the heart of Phil’s religious beliefs is an almost magpie-like hoarding of detail, rather than a carefully compiled theology, but I think it shows an attempt to understand something complex.

The passage from VALIS complements a more articulate statement spoken by Timothy Archer:

“The ancient world has seen the coming into existence of the Greco-Roman mystery Religions which were dedicated to overcoming fate by patching the worshippers into a god beyond the planetary spheres, a god capable of short-circuiting the ‘astral influences’ as it had been called in those days’.

Timothy Archer, 185

Phil is drawing on an occult reading of Christianity, which emphasised the sharing of traditional teaching from ancient Egypt onwards, a form of truth complementary to the truth of Christianity.

It also recalls the words of Symmachus, a fifth century CE Roman Senator, who said:

“Does it matter what practical system we adopt in our search for the Truth? The heart of so great a mystery cannot be reached by following one road only.”

The redeemer redeemed?

A friend told me that his wife has a trick.

While watching TV, she will comment on female stars and say something like ‘She’s not pretty”.

He sadly shakes his head. Why are women so cruel to women?

Mostly she misses the mark, but every so often she hits the spot.

While watching a documentary about Linda Ronstadt, she commented on her looks.

Her mother told her that her father had been a fan.

“But I thought my father liked more stunning beauties,” she said. “She looks so homely”.

I did not also tell her that she was often on my Spotify wrapped, is a bit of a historical crush, and I completely understand my father-in-law’s predilections.

So it was a surprise to learn that one of my favourite authors, also had a soft spot for Ms Ronstadt, identifying her not just as a foxy chick, his words, but also as a channel for divine revelation.

***

Depending on the situation, I would normally say Philip K Dick is my favourite author.

Because he was my favourite writer at a formative period of my life and more because he is better known than some of my other favourite writers.

As we mature and as we learn more and experience more, our tastes change and we question such things.

When I first read VALIS as a teenage boy, I was open to a hippy-like existence and perhaps too naive about the cost that such a lifestyle would have on people around me. Like many probably, I assumed Phil was an inveterate dropper of acid. I later learned his drug of choice, like Johnny Cash, was amphetamines.

It powered him through novels and stories at a rate that would give more elegant authors heart palpitations just to think about.

This drug intake probably led to paranoid psychosis, which may have played a role in the 02-03-74 experiences.

(Even if he had quit drugs a few years before and even tried to become a supporter of anti-drugs politicians.)

It also affected his personal life.

Phi saw himself as a “gentle saint-like sage” (Arnold, p. 62) but at times he could be controlling and violent, especially to the women in his life.

At one point, he attempted to drive a car with a close female friend into oncoming traffic and he likely lied to medical authorities to have another wife sectioned.

He hit wives several times.

He also married younger wives. Nancy, the daughter of Maren Hackett, was 19 when they married. He was 38. After their divorce, he went on to marry another similarly aged woman.

This side of his life I did not know until very recently as I began researching for this post.

But it is clear the female characters in his books are not very positive.

In VALIS, the death of two women are seen as personal attacks on the Philip K Dick character: “Horselover Fat is dead. Dragged down into the grave by two malignant women”.

***

Ursula Le Guin picked up on this aspect of Phil’s work. She wrote “The women were symbols – whether goddess, bitch, hag, witch”.

Phil wrote Timothy Archer, his final book published while alive, from the perspective of a female narrator, partly in response to this criticism.

“This is the happiest moment of my life”, he later wrote to Le Guin, “to meet face-to-face this bright, scrappy, witty, educated, tender, woman […] and it had not been for your analysis of my writing I probably never would have discovered her” (Sutin, p. 277).

***

Characters are not his strongest point, and female characters in particular are not fleshed out.

But, Phil’s heroes are almost totally flat characters, to use E.M. Forster’s phrase, defined by single traits and not psychological depth.

In other author’s work this would be a weakness, but in Phil it is a virtue allowing him to explore themes, sometimes of psychology, often to their absurd logical ends.

There are four main female characters in VALIS, three of whom were drawn from life. The ex-wife fighting for custody, Gloria who kills herself and Sherri Solvig who is dying from Cancer. The latter two deaths are treated as attacks on the Philip K Dick stand-in.

- Ex-wife Beth was based on his fifth and final wife, Tessa.

- Gloria was based on Maren Hackett, his ex-mother-in-law (fourth wife).

- Sherri was based on Doris Sauter, a close friend and neighbour, who was very ill. (She lived for years, becoming a writer and lecturer.)

Doris also inspired Sylvia Sardassa in Radio Free Albemuth. Like Sherri, Sylvia is dying from cancer and is a communicant of the (Episcoploan) Church. Unlike Sherri, she is a member of a secret, millennia old society directed by an ancient satellite. But she lacks some of Sherri’s bite.

Certainly Sherri is two dimensional, but she is a strong character, perhaps the strongest character in the entire novel.

When Sherri propositions her priest, Larry, he replies that he doesn’t like to mix business with pleasure.

He later says that he has cried all the tears he has for Sherri.

She spends her days reading about the Battle of the Kursk and volunteering at the church, where she separates the deserving and undeserving charity cases.

Sherri represents a more normative Christianity.

***

There is one other important female character in VALIS: Sophia Lampton, the two year old daughter of the rock musicians Eric and Linda Lampton.

She is the incarnation or avatar of divine wisdom, the force that broke through to Phil in 1974, and that was also experienced by his character.

Her previous avatars are listed.

Although female and non-binary messiahs have existed (or at least identified themselves as such) – Mother Ann Lee, Joanna Southcott, and Public Universal Friend – Sophia’s previous incarnations are all men.

‘I am the injured and the slain,’ Sophia tells the characters, “But I am not the slayer. I am the healer and the healed.’

This seems to directly recall the narrator of Thunder, Perfect Mind, a text found at Nag Hammadi. The narrator may possibly be the Valentinian Sophia. She speaks in similar albeit more explicit terms:

I am the whore and the holy one.

I am the wife and the

virgin. I am <the mother>

and the daughter. I am the members

of my mother. I am the barren one

and many are her sons. I

am she whose wedding is great, and

I have not taken a husband.

This text also recalls the words of the goddess Isis.

In VALIS, Sophia very clearly identifies herself as divine wisdom. She tells the other characters:

The day of Wisdom and the rule of Wisdom has come … Formerly you were alone within yourselves; formerly you were solitary. Now you have a companion who never sickens or fails or dies; you are bonded to the eternal and will shine like the healing sun itself.”

That is, she announces the coming kingdom.

If madness is a diagnosis of being counter to society’s expectation, then the healing of madness is not necessarily the healing of the individual, but the healing of society.

It is the revelation that the mad person is sane and society itself is mad.

The personal is apocalyptic.

***

This idea of female saviours is developed more fully in The Divine Invasion, a novel which most fully maps Phil’s interest with different realities and the more occult discoveries of his later years.

God has been driven out of the solar system, by a zone of evil.

The novel’s plot is driven by his attempts to re-enter the system and defeat evil, through a plot heavily drawing on the gospels.

Sci-Fi Opera Nativity.

But this is a more gnostically informed religion.

(It’s also a very good book.)

***

There are different female characters who are twinned with the male characters, providing them transcendent knowledge and ultimately salvation.

The novel ends with divine syzygy, the union of two cosmic powers, understood as male and female, although I think it is implied they transcend gender.

This again in part of the Valentinian cosmology.

(Also, Evil is represented on Earth by dangerously powerful police and immigration officials.)

It is heady stuff, but Phil focuses on the domestic scale: Marital tensions, business opportunities and music.

***

The singer Linda Fox is a massive star in one reality, but an up and coming singer in another.

Phil spends a long period, focusing on both her ethereal voice and her physicality.

“Linda wore an extremely low-cut gown and even from where he sat he could see the outline of her nipples”.

It is clear that she is based on the popular singer Linda Ronstadt, even if an actual song by the real Linda Ronstadt is later described.

“You’re no good”, one of the few pieces of authentic music mentioned in the novel alongside Mahler’s Second Symphony.

All very meta.

The Fox has her own insecurities and worries, but she is aware that there is another reality in which she is a big star.

The novel ends with Linda Fox, understanding this other reality, and defeating a form of Belial, the personification of evil.

G-d himself explains what she has done. “She has saved you. The poisonous snake is overcome … I told her that her music must exist for all eternity for all humans: that is part of it”.

The serpent refers both to the subtil beast in the garden and to the final show-down with the dragon outlined in Revelation 12.

As my more astute readers will remember, this final dragon was opposed by a woman with a child, an image that would have been familiar to followers of the goddess Isis, as well as the Virgin Mary.

In The Divine Invasion it is Herb Asher’s first wife, Rybys, who has given birth to a divine child, but he left her for the Fox.

And, it is Herb’s union with the Fox which brings to a close evil.

Male sexual desire then becomes the channel for redemption in this world, a theory that runs counter to much orthodox and gnostic Christian teaching, while sadly affiriming the patriarchal structures they support, intentionally or otherwise.

***

It is hard to read these novels in the light of what we know about Phil’s relationships with the women in his life.

At best they show an attempt to explain an experience clearly of some power and emotional truth in religious terms, but without the more normative concerns of sin.

At worst, they completely gloss or even justify misogynistic beliefs and actions.

In several of the later novels, Phil explores this theme by separating the Philip K Dick figure in the narrative from the more ‘mad’ character.

Perhaps this is a way to distance himself from a sense of culpability in evil.

It’s also a neat way to articulate the psychological damage affecting humanity.

If madness and insanity forms an important theme, then salvation and healing are the end goal of the character’s spiritual quests.

It is not a new self, but the original self, the real self, cleansed of obscuration.

‘Fat hoped that the Savior would heal what had become sick, restore what had been broken’

But it is the world he argues that is sick and it is the world itself that is saved and made new.

On this point, perhaps, his work gets close to the promise of early Christianities.

***

Throughout VALIS, the line between truth or delusion, like the Morning Star, in the industrial haze of LA, shimmers on the edge of sight and remains indistinct.

It is in such blurrage that Phil’s work gains it power.

Anyone who has enjoyed these novels, should get hold of the Nag Hammadi codices for the real heady stuff.

Blade Runner 2049: a Coptologist’s appraisal

A new visit to Blade Runner world.

Apocryphal Gospels

The new edition by Simon Gathercole reviewed.

Cover photo: Philip K. Dick (c. 1953, age 24) (Public Domain via Wikimedia)