London has many ghosts, many monsters, but none are so mysterious as the sphinges of Duchess St.

They stand in memoria to the site, in former days, of the London home of Thomas Hope, artiste extraordinaire. Although disbanded and partly demolished, 10 Duchess Street had a major impact on British art and design that is still felt today.

Thomas Hope was driven by an artistic passion, enabled by great financial resources.

He was the heir of a very powerful, rich and dangerous Scottish banking family based in Amsterdam. They had made their fortunes by lending money for the expansion of the Dutch colonial project, including plantations run by enslaved workers, as well as financially supporting European governments and rulers, including Catherine the Great. The family left Amsterdam after nearly 100 years in 1795 during the Batavian Revolution, but continued to be big players. The firm backed the Louisiana Purchase of 1803.

Although Hope was negatively impacted by the political radicalism of the time he remained broadly liberal saying he found the ‘French Revolution ‘a more promising not necessarily pro-Greek system’.

Yet, as we will see, he badly wanted to receive a British peerage, something he failed to do.

As a young man, he spent a lot of time traveling around the Eastern half of the Mediterranean in Greece, Turkey, Syria and Egypt, all then part of the Ottoman Empire. This early experience culminated in his novel Anastasius. Although essentially now out of print, it was a best seller of its day, being printed in 13 editions and translated into four languages. Sir Lord Byron was even jealous of its success.

His reputation today rests on two houses which no longer survive: the Deepdene and 10 Duchess Street, a country house and town house respectively.

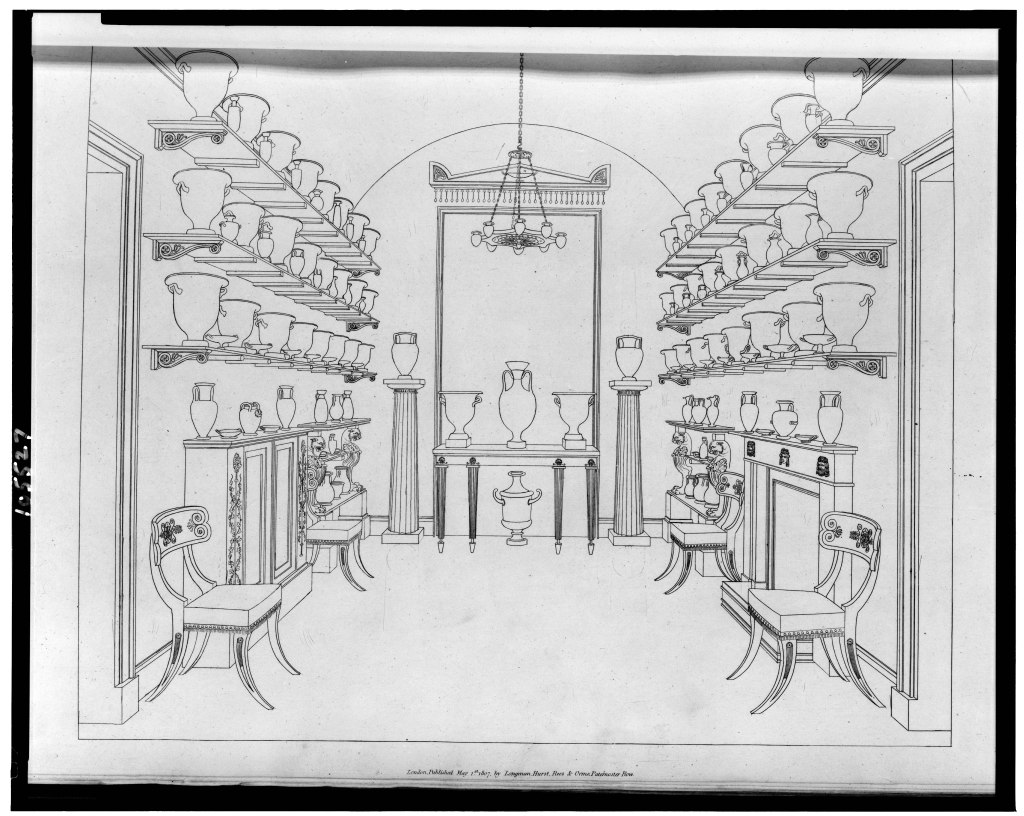

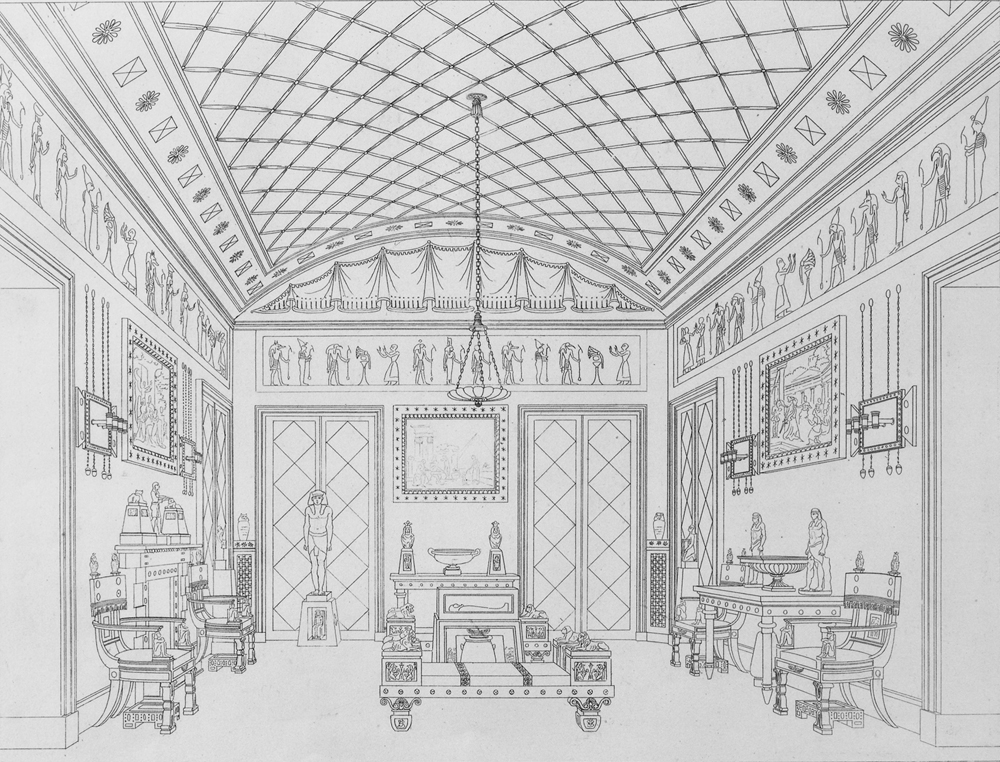

The house on Duchess Street was designed and built in 1770s by Robert Adam. Hope extensively remodeled it between 1799-1801. His guide to the property, Household Furniture and Interior Decoration, gives us the best sense of the spaces he created. Objects and rooms are alike depicted in simple line drawing and with no coloring or cross hatching, which somehow still evoke a sense of what it must have been like to visit the house.

It was designed as an gesamtkunstwerke avante la lettre, to play to all the senses. Incense was lit in the Roman galleries, while an organ played in the picture gallery. Although the drawings do not show this, Hope carefully considered the impact of color throughout. The style was neo-classical, but ornate and luxurious.

Not for him the tired classicism of a William Wilkins (of National Gallery and UCL fame).

Hope decried people who designed “houses in the shape of temples [and] have contrived for themselves most inappropriate and uncomfortable dwellings” (Watkins, 1968, 10).

Duchess Street housed one of the most comprehensive collections of Dutch Golden Age Art in the United Kingdom at the time. Hope’s brother lent him 100 of the family’s paintings to display in a specially designed gallery space with a special mahogany screen running down the middle to allow room for more art.

Hope also collected contemporary art including works by John Martin, John Flaxman and Antonio Canova. These artists were all noted for their interest in ancient themes. Hope grappled with how to display art in a publicly accessible way. This was the period of the first public museums in Europe and Hope was at the vanguard of the movement.

He also owned 750 Greek or Roman vases, ⅔ of Sir William Hamilton’s second vase collection. The collection was later split in 1917 when it was sold at auction along with many other items.

Egyptian collection

Yet, it was his Egyptian collection which most excites interest today. His collection largely came from Rome including a lion from Tiberius palace on Capri and a granite urn from Hadrian’s villa at Tivoli. He also owned a mummy in a glass case. These he displayed to emphasise their wow factor with pale yellow and bluish green, highlighted by black and of gold, to complement the objects in his ‘little canopus’.

Some of the Egyptian items, were actually not ‘Egyptian’. As David Watkins writes:

His approach was never purely archaeological. His was the subtle vision of an age of synthesis which loved to see one civilization though the eyes of another… it did not greatly matter whether his Egyptian pieces were ‘genuine’, were Roman copies, or modern copies. It was the allusive, cumulative, picture that counted.

Watkins, 1968, 48

For example, he had praised a bust of the national hero, Horatio Nelson, by the sculptor Anne Seymour Damer, a cousin to Horace Walpole) and went on to buy a bust of Mrs Freeman as Isis, now in the V&A collection. It contained two symbols of the cult to the Egyptian gods, as then understood, a lotus flower on the head and a sistrum on the base.

Yet, he was absolute discerning in his approach to Egyptian style. His description of the Egyptian room in Household Furnitutre and Interior Design continues:

Let me however avail myself of the description of this room, to urge young artists never to adopt, except from motives more weighty than a mere aim at novelty, the Egyptian style of ornament. The hieroglyphic figures, so universally employed by the Egyptians, can afford as little pleasure on account of their meaning, since this is seldom intelligible: they can afford us still less gratification on account of their outline, since that is never agreeable; at least in as far as regards the smaller details, which alone are susceptible of being introduced in our confined spaces. Real Egyptian monuments, built of the hardest materials, cut out in the most prodigious blocks, even when they please not the eye, through the elegance of their shapes, still amaze intellect, through the immensity of their size, and the indestructibility of their nature. Modern imitations of those wonders of antiquity, composed of lath and of plaster, of calico and of paper, offer no one attribute of solidity or grandeur to compensate for their want of elegance and grace, and can only excite ridicule and contempt.

Pg. 27

Hope’s playful approach can be seen in the ‘Lararium’. This Egyptian style chimneypiece contained a melange of objects from different cultures, including Egyptian and Indian figurines and a statuette of Marcus Aurelius owned by his father. David Watkins suggests that Hope would have seen the space as a family shrine. This is perhaps similar to how ancient Romans would have understood these spaces as well, containing both the family gods but also precious objects handed down the generations. Yet the setting recalls Piranesi’s designs. Indeed, Hope’s father actually bought a Piranesi chimney piece for the family’s house in Amsterdam.

This playful sense of history is best seen in the Hope furniture designs. As these have survived, we can judge their high quality finish. These were made to match the collections.

Legacy

The house points to Hope’s love of art and style and yet it may have served an additional purpose as a way for him to enter society.

Yet Hope did not understand the unspoken conventions of elite regency society. He caused umbrage when he issued entrance tickets to members of the Royal Academy, leading the gentlemen of that esteemed company to feel they were being invited not ‘to meet Company but as professional men to publish his fine place’.

In response to this, an anonymous pamphlet, in rhyming verse, was delivered to the Academy on the day of its annual dinner. Such an attack was then, as now, an act of grave dishonor in hidebound British society.

The poem is a list of personal attacks, beginning with the immortal lines:

Lo! Tommy Hope, beyond conjecture,

Sits judge Supreme of architecture(Quoted in Watkin, 1968, 10-11)

With the distance of time, we might indeed agree with this conjecture.

Many people did visit the house taking something vital from their visit.

The first thing they would have seen was a portrait of Thomas Hope dominating the grand staircase leading up to the reception rooms and galleries on the first floor.

Nevertheless activities like this may have led to the thwarting of Hope’s long-held desire for a peerage. It was also said he outright offered to buy a peerage from the Duke of Wellington. Even today, this is not quite the done thing, but many lesser Lords and Ladies have ascended to the red leather for less effort than Hope.

Yet I think we might also argue the house itself was the abiding passion that drove Hope through his life, and may have hastened his death. Hope caught a chill while directing workers to fit a skylight, which led to pneumonia that later killed him.

The two houses no longer survive and his collections were broken up after this death. This was partly because of a change in taste, and also family disinterest. Just as earlier family members had collected art, so had his own son Henry Hope however, later generations were less well disposed.

It has been claimed that the sale of Hope’s furniture collections inspired the regency revival of the 20s, as well as art deco.

The collection had an important impact on British taste and artists, as well as museum curators and designers. Compare images of Hope’s Dutch Gallery and contemporary images of the Summer Exhibtion and you will quickly note which style feels more contemporary.

Like the first witnesses of the opening of Pandora’s box, we are still in thrall to that great visionary master Hope and like them, through its power, we can sense something stronger than the divine, humanity, transcendent, immortal and beautiful.

Read more

- Watkin, David (1968). Thomas Hope 1769–1831 and the Neo-Classical Idea. London: John Murray.

- Watkin, David; Hewat-Jaboor, Philip, eds. (2008). Thomas Hope: Regency designer. New Haven: Yale University Press