A thing I will never understand, when people talk about forever homes.

As if anything lasts forever, let alone a home.

No, we are all part of a slow, imperceptible, but continuous decline.

The word forever home, makes me think of the grave.

That’s the place, we’ll stay longest and even that is not forever.

Diodorus Siculus recognised something of this in the Egyptians of his day.

They called their homes lodgings and their tombs, their forever homes.

It was part of a worldview, he wrote, that held earthly lives of no account, but put the greatest value on life after death.

We might think we recognise in this short summary something revealing about Ancient Egyptian culture.

But this, according to Rune Nyord of Christ’s Egyptology, is because classical authors like Diodorus, informed scholarly readings of ancient Egyptian for centuries.

In an important new study, he argues that a history of Egyptian beliefs in the afterlife, reveals more about the scholars and their historical contexts, than ancient Egyptians and their beliefs.

He calls for a drastic recalibration in how we approach this topic.

Make no mistake, this is a scholarly book, but it is written in a more accessible language than most.

This makes it easy for a general audience to comprehend a challenging argument that could be a paradigm shift akin to Egyptology’s ‘Feathered Dinosaur’ moment.

Turning first to the history of the history (the historiography) of ancient Egypt, Nyord argues that a major change happened during the Renaissance, when Greek texts were more easily accessible to Western scholars.

This included works by Diodorus and Herodotus, but also the Hermetica and Horapollo’s small book on hieroglyphs.

Before this, scholars relied on biblical passages and slight references in Latin authors, and Egyptian objects in cities like Rome.

After this, scholars felt they had a direct insight into Egyptian beliefs.

A close reading of these texts, highlighted two beliefs, one in metempsychosis, the transfer of the human soul to a new body after death, and one about immortality.

Writers sought to combine these theories together in ways that reflected their own Christian beliefs and contemporary religious debates.

Athanasius Kircher (1602-1680), for example, thought metempsychosis spread from Egypt.

He called it the “stupid dogma” and asked “Why the Egyptians strove so much for incorruption?”

But for him, it reflected the universalism of belief in immortality, even if corrupted.

Nyord argues that as Egyptology became ‘scientific’ in the late 19th century, it reflected contemporary beliefs in the afterlife.

The Prussian Scholar Karl Richard Lepius (1810 – 1884) invented the term ‘Book of the Dead’ for texts called in Egyptian ‘Coming out by Day’.

He claimed he could draw a map of the underworld based on his reading.

But he understood Egyptian religion in implicitly Christian terms, arguing the word ‘day’ in the Egyptian name, meant the final “Day of Resurrection, of Judgement, of Justification”.

A slightly later scholar, E.A. Wallis Budge (1857 – 1934), was even more explicit.

In a popular textbook on Ancient Egypt, published in 1899, he wrote:

“The Egyptians of every period in which they are known to us believed that Osiris was of divine origin, that he suffered death and mutilation at the hands of the powers of evil, that after a great struggle with these powers he rose again, that he became henceforth the king of the underworld and judge of the dead, and that because he had conquered death the righteous also might conquer death.”

Nyord notes the similarity to the Apostles Creed.

The historiography study ends with this ambiguous passage.

In his summary, Nyord highlights the importance of history as a way of understanding or thinking through contemporary concerns. For ancient Egypt, this was often of a religious nature.

He argues that relatively little changed, even given the massive difference in access to original Egyptian sources between the Renaissance and today. Reflecting on the historiography of Egypt will lead to questions about whether we can accept specific theories or not:

“Can we continue to speak confidently of the ancient Egyptian “afterlife beliefs” and “quest for immortality” knowing that these ideas can be traced back to the Renaissance, where they were constructed intuitively drawing on Christian concepts and a few passages from classical authors no longer regarded as authoritative in order speculatively to explain practices of burial and mummification that were known in very little detail?”

Given the focus of this book, little space is given to exploring alternative approaches.

Nyord argues that the mummification of the dead could be as much part of ancestor worship.

This argument, quickly sketched at the book’s closure, is persuasive if not interrogated in any depth. It raises important questions about the assumptions on belief and ritual that impact us all. And it makes a fascinating and insightful conclusion that demands further study and reflection from the reader.

So should we see tombs, not as forever houses, but as spaces where time meets, the living and the dead, the present and the past?

Perhaps.

But, the extent to which this argument reflects contemporary concerns, only the future can judge.

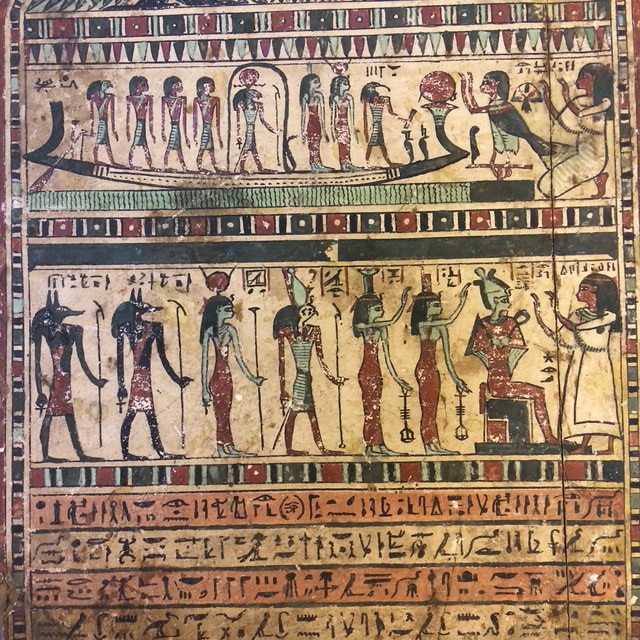

Feature image from the Tutankhamun: Treasures of the Golden Pharaoh exhibition at the Saatchi in 2019.