Egypt: Lost Civilizations by Christina Riggs

Christina Riggs’ new book on Ancient Egypt examines the long history of Ancient Egypt. It begins with a baboon statuette on the desk of Sigmund Freud. Bought in Vienna, it can now be found in St John’s Wood where the Freud family sought refuge from the Nazis. The baboon may portray Thoth the scribe god. It was made during the period when Egypt was under Roman control. During this late period, Egyptians may have sought solace in their animal gods (theriomorphic) as an “Egyptian” alternative to foreign human gods (anthropomorphic). Thoth was honoured for millennia after “the end of Egyptian religion” as Hermes Trismegistus, a sage-like magician.

Individual objects when analysed can have such a richness of meaning. Christina attempts to do this for an entire culture. Whilst she cannot read closely the millennia long history of Egypt, she nevertheless offers a deep interpretation of Egyptian’s long history that needs to be read.

The Science of Egyptology

Christina foregrounds the politics of archeology and history. “Wherever we look for the lost civilization of the Egyptians, we cannot help but find ourselves”.

Modern Egyptology has colonialist origins. This is indubitable although it is often brushed under the carpet in the public arena. Napoleon’s conquest of Egypt, the decryption of the Egyptian hieroglyphs and the publication of Description de l’Égypte are all seem as beginning the period of modern scholarship in Ancient Egypt.

Many early assumptions in Egyptology were informed by racist belief systems. The ideologues Nott and Gliddon partly based their racist “Science” of craniology on mummy skulls. This work was a historical justification for US slavery. They argued that the pharaohs were caucasian and relied on a black slave force. I have not read this work and so I am unclear whether in the minds of the authors the Hebrew slaves were black and what this meant for the progeny (including those of the House of David). I am assuming the authors were Christian. Flinders Petrie also believed in this science. The Petrie Museum in London has not shied away from this; acknowledging and critiquing this part of Petrie’s work.

Egyptology does not just perform colonial acts, but it also privileges European scholars. Ahmed Kamal, the talented scholar contemporaneous with Petrie, was overlooked for work in the European-ran Services des Antiquitiés in favour of European scholars. He nevertheless inspired an entire generation of Egyptian scholars to work in the field of Egyptology. Again the Petrie Museum has done much work on naming and praising the highly trained and scholarly Egyptian archeologists who worked with Petrie, but it is no comfort to scholars like Kamal.

Egypt in ancient texts

Christina foregrounds Medieval Arabic engagement with ancient Egypt. She provocatively argues that “Arabic scholars of the thirteenth century were better informed than their European counterparts about ancient Egyptian history – yet today it is Herodotus, not al-Baghdadi, who is quoted in every survey of Egyptian civilization”. This is true and much work needs to be done to bring this scholarship to a popular Western readership or audience.

Egypt is an unstable category in the texts of the ancient authors. Although several ancient authors engaged with Egypt, the depth of this engagement is always hard to summarise. Herodotus was the first author, who survives, to have engaged with Egyptian history. To simplify a major area of scholars dispute some modern scholars think Herodotus had a developed understanding of late Kingdom Egypt and some do not. Christian thinks that Herodotus knew a lot about Egypt, as do I. Amongst many things, Herodotus wrote how each region of Egypt revered and reviled different animal gods.

The Roman satirist Juvenal was not a historian of Egypt, but he may have picked up on some of the themes from Herodotus. In Satire 15 he portrays an Egyptian riven by factional infighting between different districts and villages which revered different animals.

Who knows not the infatuate Egypt finds

Gods to adore in brutes of basest kinds?

This at the crocodile’s resentment quakes,

While that does the ibis, gorged with snakes.

Satire 15

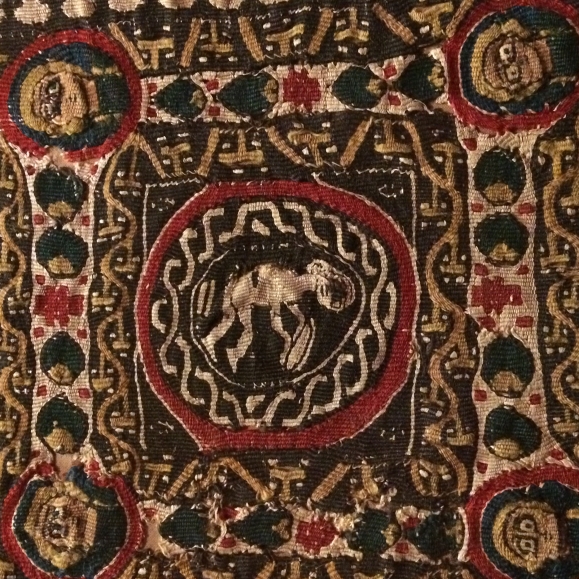

An interesting example of ancient engagement with Egypt is The Life of Severus by Zachariah of Mytilene dating from the fifth century CE. This very short biography of the young manhood of the eminent cleric Severus tells how a crowd of Alexandrian students destroyed an ancient Egyptian temple. When the crowd arrive at the temple, the altar is hid behind a false wall. After destroying this wall they enter a chamber. The statue of Chronos (possibly Geb or Sobek) is splattered with fresh blood. The chamber contains multiple statues of animals: dogs, cats, apes, crocodiles and reptiles and in pride of place the idol of the goddess Isis in her snake form (Isis-Thermouthis). This portrayal draws on images and concepts of Egypt. Even though Zachariah claims to have been an eyewitness of these events, it is unclear to what extent this passage is an accurate description of events or just a retelling of what everyone knew about Egypt from books.

Yet the Egyptians were active agents in this ambiguous portrayal of their own distinctness. As Christina argues the theriomorphic gods of Egypt may have become more popular during the period as a rejection of more cosmopolitan religions.

In terms of religion, some scholars talk about Greek gods and Egyptian gods in Egypt during this period. It is assumed the “Egyptians” would revere the “Egyptian” style gods, including the famous animal gods, and “Greeks” would revere “Greek” style gods. The god Serapis is sometimes used to exemplify this. Ptolemy I supposedly introduced the god as a Greek version of a popular Egyptian god in order to unify his new dominions. The origins of Serapis are murkier than this, however.

On closer examination the dichotomy between Egyptian and Greek breaks down. We know from inscriptions (epigraphy) that Greeks in Memphis revered the bull-god Apis before the period of Greek rule in Egypt. The Greek speaking Isidorus engaged with the rituals of the snake goddess Isis-Thermouthis at Medinet Madi, albeit praising her in syncretic terms in elegant Greek verse. It is difficult to identify ethnic groups behind different cultural expressions.

Later during the Egyptian Byzantine period and into the Umayyad and Abbasid period, the Miaphysite “Coptic” Church portrayed itself as the one true church and the national church of Egypt. In texts, like the History of the Patriarchs, the Greeks are portrayed as being punished for their false beliefs and chased from the country by the new Arab rulers.

Egypt in modern texts and art

Napoleon’s conquest of Egypt, the decryption of the Egyptian hieroglyphs and the publication of Description de l’Égypte etc. led to a burst of Egyptian inspired architecture, furnishings and flatware, although such Egyptian furniture was always a “niche taste”.

This vogue was sometimes called “Egyptomania”, but why Christina asks was the similar “craze” for Greek and Roman motifs not called a mania? “No matter how familiar it became, ancient Egypt kept a touch of the alien and other, which only a ‘mania’ could explain”. To some degree this is true. The Egyptian inspired items always had a touch of the oriental, but it may be reading too much into the word “mania”. The use of mania was lighthearted but it does reveal concerns and ideology. A comparison to the slightly later Victorian vogue for ferns called Pteridomania or Fern-Fever might reveal similarities. Again the word “mania” is tongue in cheek, but examining the literature and images reveals a concern for female sexuality which was expressed in humour.

Following the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun, a vogue for Egypt returned in the ’20s. In London Factories and cinemas were decorated in the Egyptian style. Egyptian motifs and themes can also be found on several buildings of the period. Egypt denoted luxury, excitement (exoticism) and a turn away from older styles (classicist and neo-gothic).

Artists of the “Harlem Renaissance” also engaged with Egyptian themes and artistic motifs, at the same time. For the black artists of the ’20s, Christian writes Ancient Egypt was an unstable category. Drawing on both religious motifs (originating with Exodus) expressed powerfully in hymns and spirituals, and also the excitement of the Tutankhamun discoveries artists like Aaron Douglas, Meta Warrick Fuller and Lois Mailou Jones created powerful and inspiring art of the black experience which is often sidelined in favour of “Egyptomania” art-deco architecture.

Christina focuses on Egypt’s own engagement with its past. From the Al-Firawnuya art to El Zeft’s portrayal of Nefititi in a gas mask, modern Egypt has engaged with its ancient past as deeply as Western counties.

Egypt before Napoleon

If I had one small criticism, I would have liked to have seen more about European engagement with Egypt pre-Napoleon. This is because I do not know much about this period of study. It is likely that the two main sources for Ancient Egyptian history during this period were the classical authors and the Bible. In his list of fallen devils in Paradise Lost, Milton describes the Egyptian gods in tones resembling both Juvenal and Moses.

After these appeared

A crew who, under names of old renown—

Osiris, Isis, Orus, and their train—

With monstrous shapes and sorceries abused

Fanatic Egypt and her priests to seek

Their wandering gods disguised in brutish forms

Rather than human. Nor did Israel scape

Th’ infection, when their borrowed gold composed

The calf in Oreb; and the rebel king

Doubled that sin in Bethel and in Dan,

Likening his Maker to the grazed ox—

Jehovah, who, in one night, when he passed

From Egypt marching, equalled with one stroke

Both her first-born and all her bleating gods.

Another interesting example of this secondhand engagement with Egypt is this small ceramic sphinx from the Fitzwilliam Museum (Cambridge).

Sphinx with a lady’s face (maybe actor Peg Woffington) c1750-55 @FitzMuseum_UK #reception Georgian #egyptomania pic.twitter.com/9MPszC2Kxr

— Simon Bralee (@Braleebatch) November 14, 2017

It predates Napoleon’s Invasion of Egypt, but shows an engagement with Egypt as the land of theriomorphic dieties. The sphinx was popular in Greek areas and so may have nothing to do with Ancient Egyptian. The Sphinx soon became an obvious symbol of Ancient Egypt however, as these sphinxes outside residential houses on Islington demonstrate.

Sphinxes in Islington, riddle me this #egyptomania pic.twitter.com/H1R2g8DUAj

— Simon Bralee (@Braleebatch) September 29, 2017

Summary

Otherwise this book is brilliant. It covers an immense subject field and balances depth and brevity. It challenges us to rethink assumptions and beliefs and question the extent to which colonial thoughtprocesses still inform our reading of Egyptian history.

It is a stirring call for the decolonisation of Ancient Egyptian history.

3 replies on “Egyptomaniacs”

[…] The exhibition is good but I can’t help but pick faults with a few of the concepts here. For example, the curators seem to define the modern as Late Twentieth Century and Western (largely white and male) and the classical as Greek and Roman. This means the exhibition fails to examine the rich cultural forms that developed across the ancient world from interactions between cultures such as, for example, the art from Alexandria which grew from a engagement between Egyptian and Greek and Roman cultures. A small Isis-Thermouthis terracotta would be more valuable than Damien Hurst’s ironically vulgar Medusa. The exhibition also fails to examine the vexed engagement with the classical from non-elite groups, such as Kemetism. […]

LikeLike

[…] The book tells a history not just of ancient Egypt but also the western study of Ancient Egypt. Unlike some popular historians, Deary foregrounds topical questions on historiography. The colonialist and racist ideology of some early practitioners is explicitly examined and condemned. The book discusses the appropriation of ancient artefacts and the reality behind early excavations. Most refreshingly of all, Deary tells what might be a new history of Egypt for some of his readers without the over excitement of Dan Brown. The real conspiracy behind the study of Ancient Egypt is not that aliens designed the pyramids but that early archaeology was predicated on racist lines. […]

LikeLike

[…] Ancient Egypt by Christina Riggs […]

LikeLike